In a dimmed room Kurt Weston stared intently at the photography negatives of beautiful models. He was working in the dark room of Pivot Point International, a beauty school in Chicago that produced fashion catalogs, but he dreamed of one day taking the pictures he was developing.

On the weekends Kurt worked with models and makeup artists for free to build up his photography portfolio. His bosses eventually saw his work and used his images to fill the small spaces in the catalog.

His photos became wildly popular around his office. From the time he began working at Pivot Point in 1987 to 1988, Kurt rose in rank from photo developer to Pivot Point’s lead fashion photographer.

Now behind the camera, both calling the shots and taking them, Kurt began traveling to Europe to photograph models. He met the directors of the big names in the beauty industry, and worked side by side with them and earned his own celebrity in the field.

Nothing could bring him down, he was at the top of his game. Except for a cold he had recently developed –– or what Kurt thought was a cold. A cold that wouldn’t go away.

The coughs never stopped. All night, all day, Kurt would cough. After not seeing a doctor for 10 years, he decided it was time to get checked out. Kurt went to an allergist where he was pricked and poked with little needles. He had to wait a few days for the results, but it didn’t even take a day for Kurt to wake up in a sweat soaked bed with a raging fever. Something was wrong — this wasn’t just a minor cough. This was something big.

Kurt thumbed through his insurance catalog to find a doctor near him and was in the doctor’s office the next day. With a cold stethoscope pressed to his chest, Kurt breathed in and out. Fluid sloshed inside his lungs. The doctor ordered X-rays. He told Kurt he had pneumonia but he needed to do blood work to determine what type.

The doctor sent Kurt home with antibiotics, but things continued to get worse. After ten days passed, out of breath and unable to walk from the pneumonia, Kurt asked his sister to take him to the hospital for the results.

The doctor walked into the room with a stern look on his face. “Is it OK if your sister hears what I have to tell you?” he asked.

“Yes,” Kurt replied softly. “She’s my sister. Whatever it is you have to say to me you can say in front of her.”

“I have some very bad news,” the doctor said. “You have full-blown AIDS.”

Kurt’s sister wrapped her arms around her ailing brother and wept with him. A normal person’s T-cell count is roughly 1,000 or above, Kurt’s was three. He was wheeled into the hospital to live out what they thought would be the last days of his life. He was 31.

When Kurt first entered college in 1977, he was working on his Bachelor of Science; but his real passion was in the arts. Photography inspired Kurt, but his parents told him they wouldn’t support him if he studied art. Kurt received his first bachelor’s degree in 1979, a B.S. in Fashion Merchandising. Toward the end of his time at Northern Illinois University, Kurt began to engage in risky sexual activity. It was then, the doctors believe, that Kurt contracted the HIV virus, 10 years prior to his AIDS diagnosis.

After feeling unfulfilled at his job as a fashion merchandiser, Kurt decided to go back to school at Columbia College to study photography. His experiences at Pivot Point fueled his passion for the art, but it all came crumbling down after he survived his four-day hospital stay to treat his first bout of AIDS related pneumonia.

In the early ‘90s AIDS and HIV were just beginning to be treated. People thought of the virus as a gay disease; “the gay cancer” some would call it. The ‘90s were a time when many people who had contracted HIV in the ‘80s, like Kurt, were beginning to die from lack of treatment.

“Do you want to go back to work?” the doctor asked Kurt.

“Well what else am I going to do?” Kurt replied. He couldn’t imagine his life without photography. The doctor told him he could go back to work if he wanted, but to keep quiet about the AIDS.

Kurt went back to work and stayed quiet about his diagnosis. He never regained his weight after the pneumonia and began taking AZT, the only drug available in the early ‘90s for the treatment of AIDS, but the AZT only made Kurt feel sicker. While at work he’d struggle to fight the nausea and headaches while trying to keep everyone focused on the shoots.

Rumors spread that he had the disease and as time went on it became harder to hide. All Kurt wanted to do was curl up into a ball and sleep.

After working for two more years, it became too much. Kurt had battled his third bout of pneumonia, but the drugs weren’t working.

He had to quit his job and go on disability. Two weeks after going on disability Kurt developed another opportunistic infection.

Purple lesions began to develop on Kurt’s body, a physical manifestation of the disease that was killing him. People would whisper under their breath, “that guy has AIDS,” or run away from him in the grocery store. Kurt was beginning to feel like a monster.

But rather than sitting at home wasting away he decided to do something positive with his life. Kurt created a support group called Surviving with AIDS Network (SWAN) in 1993.

At the SWAN meetings members talked about alternative ways they were trying to combat AIDS, such as ozone therapy and herbal remedies. Some of the makeup artists Kurt used to work with would come in to show the SWAN members how to do their makeup to cover up the lesions on their faces and bodies.

Kurt tried some of the therapies himself. He tried ozone therapy where he stayed at a facility in New Mexico for ten days. The doctors injected ozone gas into his veins; the ozone molecules broke apart and filled his body. It only made him sick, it wasn’t a cure but it did, for a time, increase his T-cells.

Years passed and the pharmaceutical drugs weren’t working.

Kurt began to see his SWAN friends succumb to the disease. They were dropping like flies. One after the other, all of his friends were dying. He would sit with them in their hospital rooms. The anguish on their faces mirrored his, he was not only watching his friends die, but himself as well.

Toward the end of 1993 Kurt began to develop another opportunistic infection called Cytomegalovirus (CMV), a relatively common virus that can be treated with drugs, but because Kurt’s immune system was so weak, the CMV began to destroy the retinas in both his eyes.

He was going blind.

‘This is it,’ he thought. ‘My life is fading, my vision is fading, there’s going to be nothing for me to live for anymore.’

The doctors started him on Ganciclovir, a drug to treat the CMV. IVs were inserted into Kurt’s arm and hung there day after day. They connected to a tube where Kurt inserted the Ganciclovir twice a day for two years. The Ganciclovir wasn’t working, so the doctors put Kurt on another drug called Foscarnet, but that didn’t work either.

After three years of taking the toxic drugs, doctors decided to combine them to try to give Kurt a little extra time.

For sixteen hours a day Kurt wore a backpack filled with medicine –– Ganciclovir on one side, Foscarnet on the other. The backpack held a mixer that combined the drugs and pumped them into his thin, ever-ailing body.

Kurt knew he wouldn’t live much longer. When his brother called him from Brea, Calif. and asked him to move in with him he agreed. Chicago weather was always so dreary; the warm California weather would do him good.

When Kurt moved to Orange County in 1995, none of the medications were working. His doctors told him he probably wouldn’t live six months –– the CMV would eventually take over and kill him.

But three months later pharmaceutical companies began developing drugs that combined all of the new AIDS treatment that could fight the virus at different stages in its life cycle. Kurt was put on a new AIDS cocktail of medicine, and he began to see the improvement he had been waiting years for.

His T-cell count started going up. The doctors told him his viral load was decreasing. Eventually he stopped taking the Ganciclovir and the Foscarnet. He took the IV out of his arm, and his lesions disappeared. He wasn’t going to die anymore.

As he regained his health, Kurt’s desire for photography came back, but his eyesight never improved. He went to the University of California, Irvine medical center to try and get back what the AIDS had taken. The doctors put Kurt on another drug meant to help him regain some of his eyesight. But the experimental drug did the opposite, causing what was left of his retinas to become completely inflamed.

Although Kurt had already lost a significant amount of his vision, this drug did the final number on his eyes. It caused him to go completely blind in his left eye and he lost the central vision in his right eye.

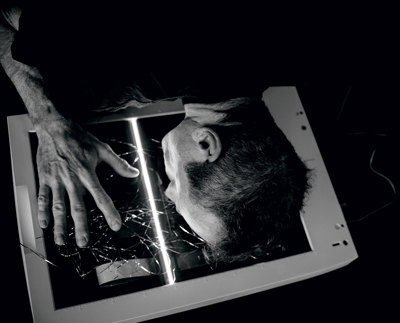

With his health partially restored, but with only a small amount of vision left, Kurt had to figure out how he was going to live the rest of his life. Photography was on his mind. He still had a little vision left, a small window of light to see the world through. Kurt went to the Braille Institute to learn how to use low vision devices: thick lensed glasses, monoculars, magnifying glasses, Kurt left the Braille Institute with a small backpack filled with devices to help him see and to help him take photos and edit them.

With his vision tools in hand, Kurt decided to go back to school to get his master’s in photography. He entered Cal State Fullerton’s master’s program in 2005, after learning to utilize the vision tools, a walking cane and his big, fluffy, white seeing-eye dog, Ambros.

Kurt’s final show as an MFA student hung in the West Gallery at CSUF in 2008. “Hearts of a Silent Age” included photographs of the elderly, some about to die, some simply aging. The breathing tubes and the endless medication resonated with Kurt. He had been where they were, younger of course, but Kurt had seen death, shook its hand and walked away.

His art had transformed from taking pictures of beautiful, made-up models to taking photos of the elderly. Their wrinkled hands, skin spots and earned imperfections contrasted with Kurt’s earlier work,

a manifestation of what his own life had transformed into.

A week after Kurt took down “Hearts of a Silent Age,” and right before he was set to graduate, he felt a pain in his abdomen, his appendix had burst. He was rushed in for surgery, but it wasn’t only his appendix. Kurt had cancer.

He was diagnosed with Pseudomyxoma Peritonei, a rare form of cancer that begins in the appendix. He walked across the stage at his graduation with fresh stitches and bandages from surgery.

‘I lived through AIDS and blindness, I got my master’s degree, and now I’m dying of a rare form of cancer,’ he thought.

Kurt’s sister convinced him to contact a psychic who told him he would survive his cancer, but he needed to get out in nature. So he did, and he brought his camera with him. He shot a series called “Seasons in a Prayer Garden,” that showcased the vibrant colors of the leaves in fall, and blossoms of flowers in spring. In 2010 Kurt won the Arts Orange County artists of the year award.

Five years after his diagnosis with cancer, Kurt hasn’t developed any more tumors. He still sees a specialist at the University of California, San Diego where he is being treated, but Kurt is surviving.

To this day his left eye is covered by a black eye-patch, he takes eye-drops every day, swallows countless pills to treat the AIDS, and visits his doctor at UCSD every year for his cancer. But his work, “Seasons in a Prayer Garden,” “Hearts of a Silent Age” and his most famous, “Blind Vision,” has been sold and shown internationally in museums, and won him awards such as OC Metro magazine’s artist of the year. On Nov. 30, 2013, Kurt married his partner of 13 years, Terry.

After wading through a life of pain and hardship and with his vision almost completely gone, his life now, like the flash of a photograph in a dark room, has never been brighter.